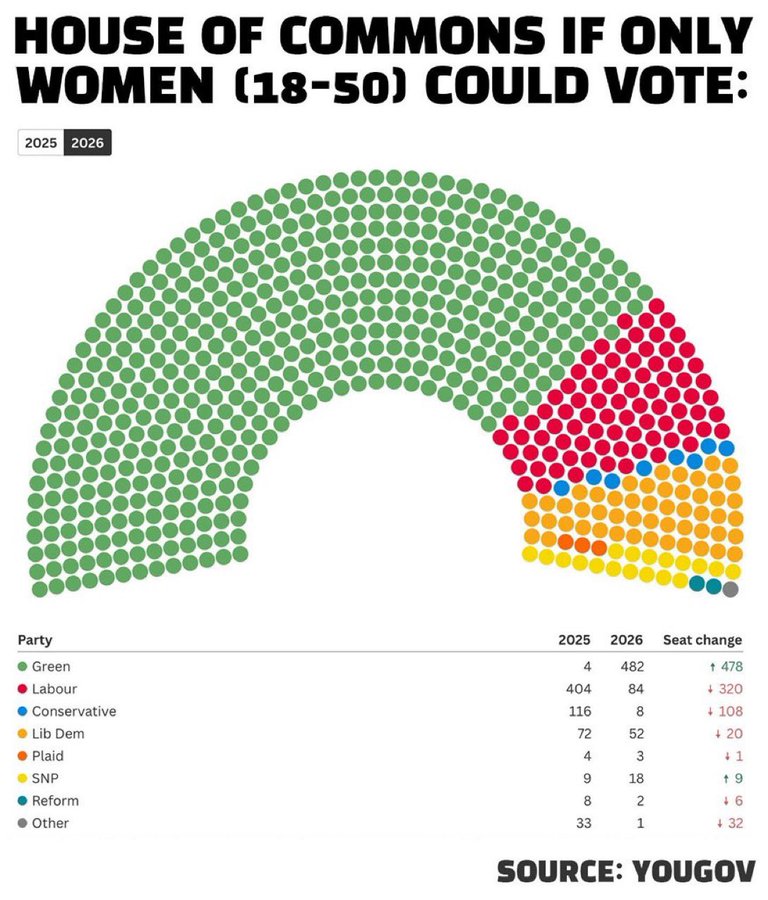

If, in elections to the British House of Commons, only women aged 18 to 50 were allowed to vote, the country would wake up in a very different political reality. According to a YouGov poll, the simulated composition of Parliament would be almost spectacular: roughly three quarters of the seats would go to the Green Party of England and Wales and, together with the Labour Party, the Greens would hold close to 85% of the mandates. Conservatives and right-wing parties would be pushed to the margins.

This is, of course, a hypothetical model. But it strikingly illustrates how far the electoral preferences of men and women, especially younger voters, have diverged. In recent years, in the United Kingdom as in many countries across Europe and North America, a durable gender divide has taken shape. Women are increasingly voting for left-wing parties, while men are turning more often toward the right or right-wing populist formations.

This fracture can be explained by several factors. Economics plays an important role: women are more likely to work in sectors where public support is crucial, from education to healthcare. Social policies from childcare to labor protections directly affect their daily lives. Climate policy is also central: women more frequently report concern about the environmental future and support strict decarbonization measures.

Yet the issue goes beyond social protection or environmentalism. Green parties in Europe have long ceased to be merely environmental movements. In the United Kingdom, the Green Party of England and Wales has become the standard-bearer of a strongly progressive agenda, ranging from ambitious climate policy to questions of gender identity, migration, and the transformation of the economic model. In doing so, it has occupied political ground once held by more traditional left-wing movements. In several European countries, activists from 1970s leftist organizations have indeed moved into green party structures, shifting the rhetoric from class struggle to sustainable development and minority rights.

On the other side stand young men. They more often express dissatisfaction with economic stagnation, rising housing costs, and a perceived loss of status. For some, conservative and right-wing parties provide a channel through which to articulate this frustration. The result is a paradox: the younger generation as a whole is becoming neither “more left-wing” nor “more right-wing.” Instead, it is splitting along gender lines.

On a broader scale, this dynamic could become one of the main axes of political conflict in the years ahead. Western democracies have already experienced class divides, followed by regional and cultural fractures. Now, the gender factor is becoming increasingly prominent.

The British case is particularly revealing, as the United Kingdom often anticipates trends that later spread across Europe. The House of Commons is, of course, elected by the entire electorate. Yet the very plausibility of such a scenario, with 75% of seats going to a single party positioned at the far left of the political spectrum, points to a profound transformation of the political landscape.