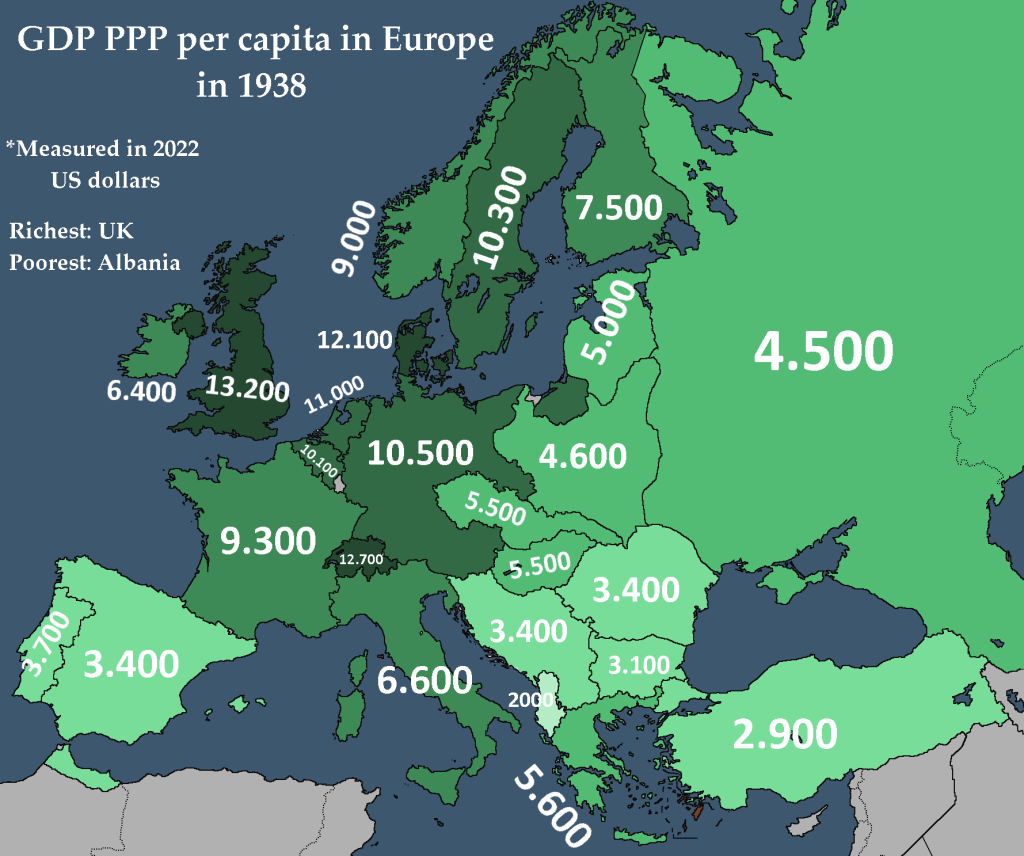

Discussions about the development of European countries, whether Russia, France, Germany or the Balkans, traditionally refer to 1913 as a starting point. It is this pre-war frontier that is often considered the last relatively ‘normal’ stage before a series of twentieth-century catastrophes: two world wars, revolutions and totalitarian experiments. However, an alternative starting point could be 1938 – on the eve of the Second World War, but after the Great Depression and the first waves of industrialisation and socio-economic reforms.

Of particular value in this context is the map produced by the Belgian-Swiss economic historian Paul Bairoch, a renowned researcher of global economic inequality, a collaborator of Fernand Braudel, and an advocate of alternative ways of measuring development. His map shows per capita GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) constant 1960 dollars. This approach captures more accurately the real differences in living standards between countries.

If we compare countries in 1938 and today, we can see that most have maintained their relative positions. That is, there is indeed a ‘historical track’, a line of development along which the state moves regardless of the change of systems and epochs. Those who were poor, in many respects remain so in the XXI century. And vice versa.

However, there are some striking exceptions that deserve special attention.

Spain: leaping up after the war

In 1938, Spain was poorer than the USSR, not surprising given that a bloody civil war was raging in the country at the time. Nevertheless, Spain made economic leaps in the post-war decades, especially during the “Spanish Miracle” of the 1960s and 1970s. Today it is a country with a developed economy and a high standard of living, despite internal contradictions.

Austria: breaking out of its niche

Austria, traditionally associated with Central Europe and the post-Habsburg space, was also able to overcome the limitations of its historical trajectory. Whereas in 1938 it was only a moderately developed industrialised country (also due to losses after the collapse of the empire), today it is one of the most prosperous economies in Europe, successfully integrated into the EU.

Norway: a leader without oil

A particularly surprising revelation is that Norway in 1938 was the richest country in Europe by PPP. This is even before the discovery of oil and gas fields in the North Sea. Norway’s economic success in that era is probably due to a combination of a highly organised society, social capital, low levels of inequality and sound institutional policies. The foundations were already laid for what later became known as the Nordic model, combining high quality of life, sustainable growth, environmental friendliness and social equality.

Poland and the bonus of industrialisation

The Polish case is also interesting. In 1938 Poland was poorer than the USSR. However, after the Second World War it received a very powerful industrial impetus due to the annexation of German Silesia – the second industrial region of Germany after the Ruhr. Poland also received a significant part of East Prussia, while the USSR received only its north – the future Kaliningrad Oblast. This territorial ‘gift’ became the basis of Polish industrial growth in the post-war years. However, the price for this was high: according to historians, about 1.2 million Germans were expelled or exterminated in the process of ethnic cleansing in Silesia and Prussia, but this is a separate page of history.

The history of the development of European countries is not chaotic; it is largely predetermined by their position in the economic landscape of the past. The year 1938, as an intermediate point between the two world wars, shows how firmly the countries are ‘sitting’ in their historical rut. But some of them, like Spain, Austria or Poland, managed to get out of it – at the cost of reforms, successful foreign policy decisions or territorial gains. And Norway’s experience serves as a reminder that even without natural resources, it is possible to become a leader if the social and economic model is properly built.