The recent Democratic Party primaries in New York were an unexpected but illuminating sociological experiment. At the centre of attention was candidate Mamdani, a politician with very left-wing views by American standards, who would be a typical social democrat in Europe. The results of the voting give us a new perspective on the question: where can the left look for electoral support today?

Who supported Mamdani?

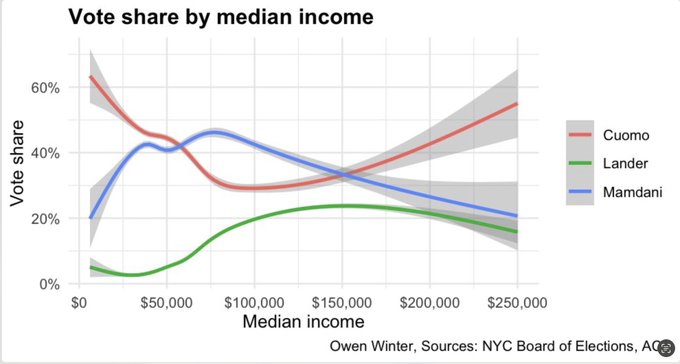

The greatest support for Mamdani came from the lower middle class. A stratum that, in a metropolis like New York, has become perhaps the most vulnerable. These are people who work but live on the edge of survival. Their income is in the range of $50-70 thousand a year, which is not enough for a more or less comfortable life in the city, where the cost of living has long gone beyond reason. Among them are freelancers, platform workers, part-time workers. Many of them live in a state of constant instability: they have no savings, no social guarantees, no insurance. This is the so-called precariat – a new urban poverty, not labelled as ‘poverty’ in the usual sense, but lacking a solid economic foundation.

It was this group that voted en masse for Mamdani. A politician who talked about redistribution of resources, labour protection, rent control and the rights of wage earners. That is, he raised topics that directly affected their daily reality.

Who voted against?

Interestingly, the poorest and richest voters were united in their support for Mamdani’s main rival, Cuomo. This may seem paradoxical: after all, Mamdani is in favour of social justice. So why did those living on welfare vote against him?

The answer probably lies in fear of redistribution. For the poorest voters living in public housing, on ration cards and other forms of assistance, the new left-wing policies may be perceived as a threat. After all, if resources are redistributed in favour of the working precariat, some benefits could be renegotiated. Supporting Cuomo is perhaps a rational choice in favour of maintaining the status quo.

As for the rich, their opposition to Mamdani is obvious: for them, leftist ideas always mean risks, from higher taxes to restrictions on the real estate market and corporate activity.

This episode shows that today the main support base for the moderate left is not the poorest, but the working lower middle class. It is this category that clearly feels that ‘the system doesn’t work’, but they don’t want handouts, they want opportunities, labour protection, decent housing and health care. The politics of the left today should be directed precisely at these people. This is not the ‘traditional proletariat’ of the 19th century textbooks, but it is not the classical poor either. This is the new working periphery of the post-industrial metropolis, which needs a voice and political representation.