In the past few months, global markets have observed sustained rises in long-term government bond yields. The phenomenon is explained by a mix of factors ranging from elevated inflation and fiscal imbalances all the way to the policy changes by central banks. However, the most significant drivers are the increase in the budget deficit and the reversal of quantitative easing (QE) programs.

For more than a decade, QE programmes have been a powerful anchor for yields: massive central bank purchases of government bonds artificially held down their yields, squeezing the risk premium. However, as these programmes have been wound down (and in some countries even reversed to quantitative tightening, or QT), the cumulative effect of QE is gradually fading.

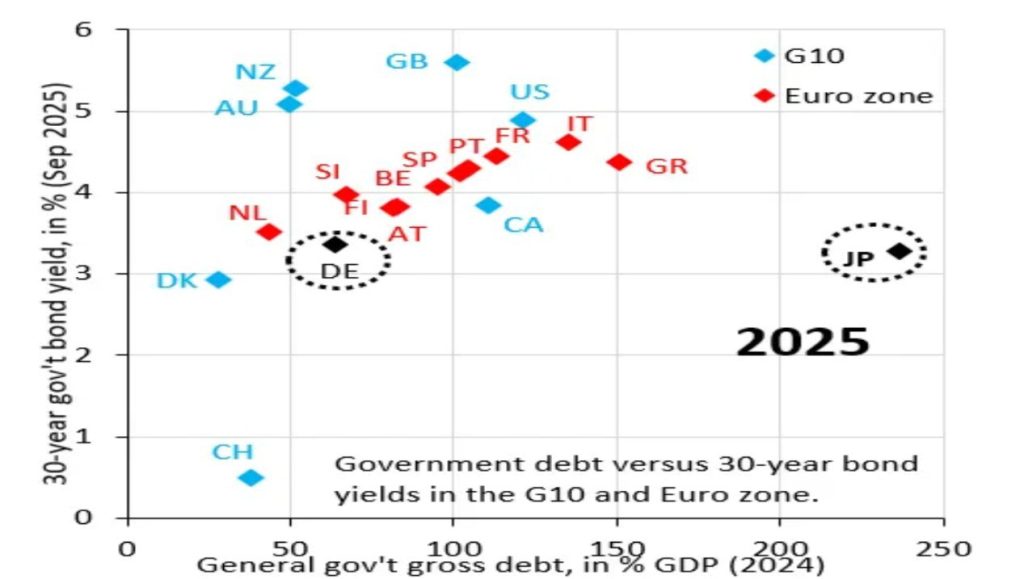

A graph comparing the yield on 30-year government bonds and gross government debt (as a percentage of GDP) clearly shows that as the effect of QE evaporates, the size of government debt comes to the fore.

Today, government debt servicing costs are becoming comparable to the costs of individual sectors of the economy. Interest payments on public debt alone, at 2% of GDP, are enough to bring the country close to Portugal and slightly behind Greece (2.4% of GDP) in this respect. By comparison, in Germany, with a public debt of around 60% of GDP, interest payments account for only 0.9% of GDP. Even a relatively small difference in debt burden significantly changes the structure of budget expenditure.

The eurozone presents a mixed picture. Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands will continue to borrow at favorable terms thanks to their good reputation. However, Italy, Spain and Portugal are seeing rising risk premiums, and they are the first ones to feel the cost of borrowing rise as their debt mounts. In the absence of a full-fledged fiscal union, this difference can only increase.

Japan remains an exception. With public debt at around 240% of GDP, its bond yields remain among the lowest in the world. This is because the vast majority of the debt is being held by domestic investors, and the Bank of Japan continues to control the yield curve, artificially limiting the rise in interest rates. But even here, policy pressure has been mounting over the last few years: an end to the ultra-easy monetary policy is becoming increasingly inevitable.

Thus, over the medium term, government bond yields will remain under increased pressure, especially in highly indebted nations and those with low confidence in economic policy.