In the European public space, an increasingly anxious narrative has taken hold in recent years, centered on the prospect of a rollback in trade with the United States and China, deglobalization, and the breakdown of established supply chains. Yet a look at long-term historical statistics makes it clear that this framing of the problem is largely misguided. For nearly two centuries, Europe and its immediate surroundings have developed above all as a largely self-sufficient economic space.

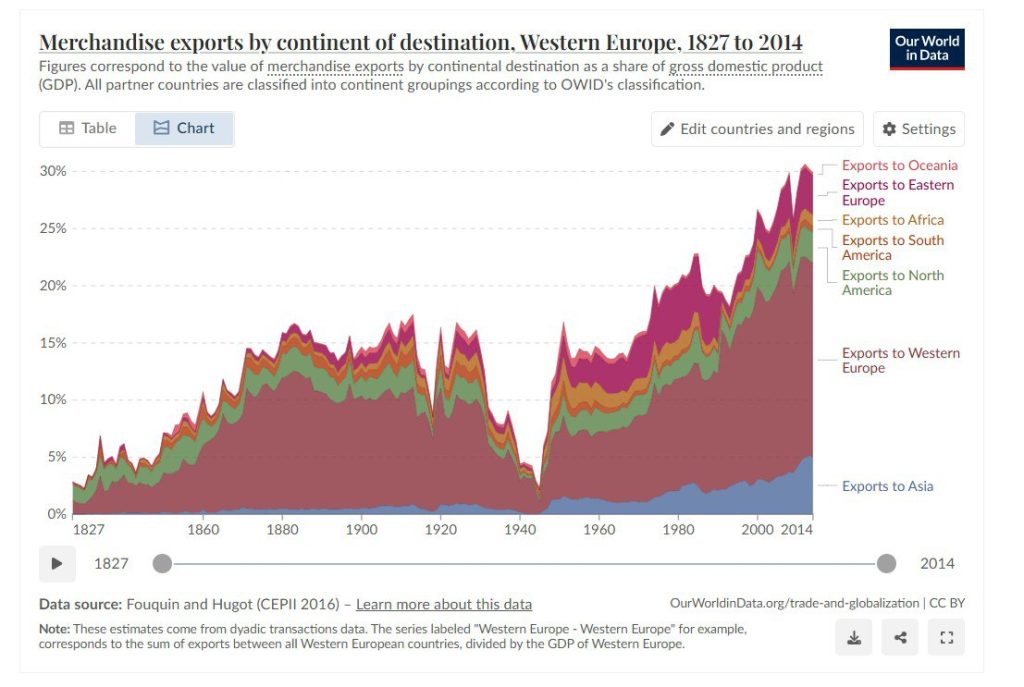

The presented visualization of Western Europe’s exports by destination from 1827 to 2014, expressed as a share of the region’s total GDP, illustrates this point with particular clarity. It refers to “classical” Western Europe prior to its eastern enlargement. The chart clearly shows that from the nineteenth century to the present day, the growth of Western European trade was driven to a decisive extent by exchanges within the region itself. Even at the height of globalization, external markets played a secondary role compared to intra-European cooperation.

In 2014, total exports from Western Europe amounted to about 30.6 percent of its GDP. Of this figure, nearly 18 percent of GDP came from trade among Western European countries themselves, or roughly two thirds of the region’s total trade. Exports to Asia accounted for around five percent of GDP, while those to North America reached only 2.7 percent. Thus, even under conditions of an extremely open global economy, Europe remained above all an economy structured around internal exchange. It is also important to recall that the data in the chart end in 2014. It was precisely after that point that trade within the EU expanded sharply thanks to the countries of Eastern Europe. In practice, this means that the share of intra-European trade today is even higher than the visualization suggests. Fears of a supposed “loss of external markets” therefore appear all the more strange given that Europe’s internal economic space has only strengthened over the past decade.

If one moves beyond a narrow focus on Western Europe and considers the continent as a whole, the scale becomes even more striking. The GDP of the European Union in 2025 is estimated at around 18.8 trillion dollars. To this figure it is logical to add the major European economies outside the EU but deeply integrated into the continental economy: the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Norway. Their combined GDP exceeds 5 trillion dollars, bringing the economy of “greater Europe” to roughly 24.2 trillion dollars, even without counting the smaller states outside the Union.

Yet this is still not the limit. Europe has a vast periphery that is historically, culturally, and economically closely connected to it. The combined GDP of Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Belarus, and the countries of the Caucasus amounts to around 4 trillion dollars. Added to this are the countries of the southern Mediterranean: Israel, Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, with a total GDP of about 1.5 trillion dollars, not to mention the deferred reconstruction potential of Syria, Lebanon, and Libya. Taken together, the GDP of the entire European macro-region approaches 30 trillion dollars. This is comparable to the size of the U.S. economy and about one and a half times larger than that of China in 2025.

The demographic factor is no less important. The population of the EU and the countries closely integrated with it stands at about 550 million people. Adding the populations of Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and the Caucasus brings roughly another 200 million. Turkey contributes nearly 90 million inhabitants, while the Mediterranean countries of North Africa add around 200 million more. In total, this amounts to over one billion people. Against the backdrop of China’s rapid demographic decline, the European macro-region is, in the medium term, in a position not only to match China in population, but potentially to surpass it.

In light of these figures, a rational conclusion suggests itself: it is precisely the European macro-region that objectively possesses one of the strongest future potentials. At the same time, the United States is increasingly eroded by internal conflicts, Trumpism, and the radicalization of the MAGA movement, while China is sinking deeper into demographic decline and remains governed by an ever more gerontocratic elite.

Admittedly, the European macro-region also contains its own destabilizing forces, but this is a matter of political will and governance choices rather than a lack of objective potential. Europe needs to deepen and expand its internal integration, including with the countries on its periphery, work toward a sustainable peace in Ukraine, and pragmatically develop its external relationships from a rising Kazakhstan to Canada, which is feeling increasingly uncomfortable amid U.S. political turbulence. Under such conditions, Europe is capable of once again becoming an autonomous center of power in the world. Objective economic and demographic parameters are already working in favor of this scenario today.