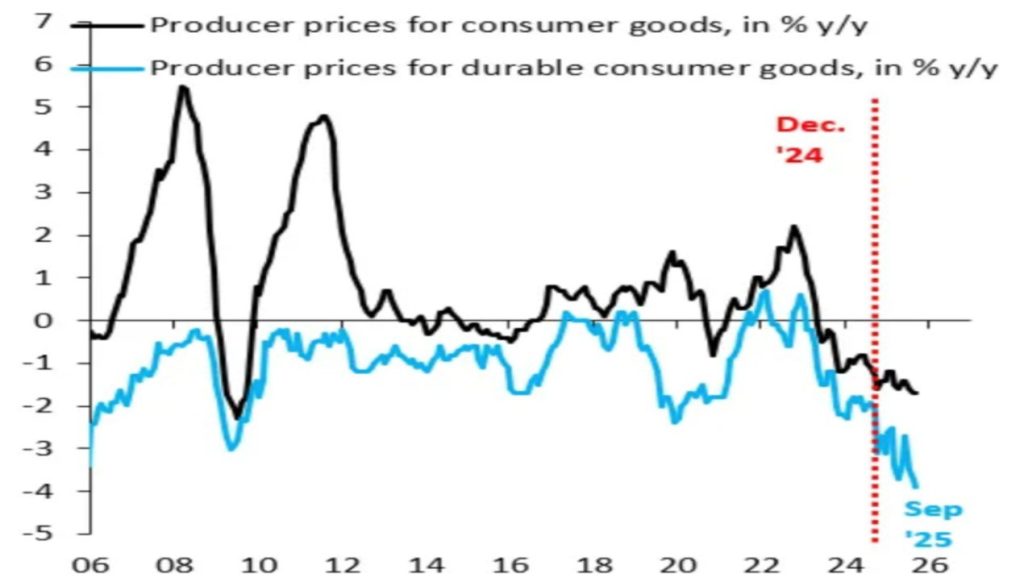

La Chine entre dans une phase de déflation. Il y a quelques années encore, cela semblait impossible pour une économie fondée sur les exportations et une expansion agressive. Le graphique montre comment l’indice des prix à la production chute rapidement en territoire négatif. En septembre 2025, le coût des biens de consommation durables produits en Chine avait baissé de 3,9 % par rapport à l’année précédente. Cette baisse a coïncidé avec l’introduction de nouveaux droits de douane à grande échelle sur les importations chinoises aux États-Unis.

The tariff shock became a catalyst for processes that had been brewing within China for a long time. The export-oriented model, based on large volumes and low costs, began to fail. When the American market became less accessible, exporters faced a dilemma. The production system assumes the movement of goods without the accumulation of large warehouse stocks, so stopping the conveyor belt means stopping working capital. Therefore, the only way to absorb the impact of tariffs and maintain production capacity utilisation is to sharply reduce prices, stimulating demand domestically and in alternative export markets. Chinese manufacturers began to sell below cost, effectively sacrificing profitability in order to maintain turnover.

This is where what could be called the ‘Japanese track’ begins. Three decades ago, Japan also hit a deflationary wall: an ageing population, limited domestic demand, a high propensity to save, and a decline in investment appetite. Some strategists at the time believed that the country was experiencing a temporary slowdown, but these temporary measures stretched into decades of economic stagnation, which later became known as the ‘lost decade.’ China is now following a similar trajectory: its population is ageing rapidly, domestic demand is weakening, and young people are exercising financial caution, lacking sufficient confidence in the future.

The difference between Japan and China lies in scale and geopolitical context. Japan experienced deflation in a world of open markets. China is facing it in an era of trade wars, deglobalisation, and the redistribution of production chains. To keep the economy afloat, the state is forced to subsidise corporations more and more, increasing the dependence of business on political decisions. This contradicts the very logic of a competitive market and pushes China towards a managed economy model.