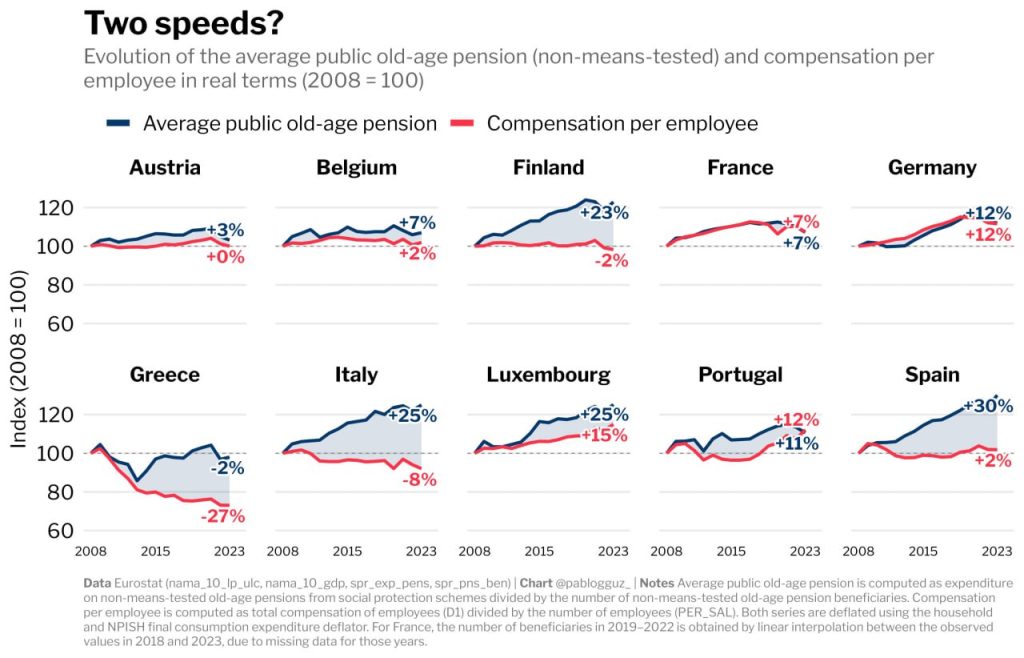

Since 2008, a steady trend has emerged in a number of European countries: the average state old-age pension in real terms is growing faster than compensation for labour. The graph clearly shows that in Spain, Italy, Finland and Luxembourg, pension payments are growing significantly faster than wages, and in some cases even against a backdrop of declining wages. Even in more stable economies, such as Germany and France, pensions are growing at least at a comparable rate, and in some years faster than the incomes of working citizens. This directly contradicts the basic principle of a distributive pension system, in which the level of payments to the older generation should be determined by the capabilities and productivity of the working-age generation.

Essentially, this dynamic creates a new type of socio-economic imbalance. The generation that has already retired from active economic life finds itself in a more secure and stable financial position than those who are keeping the system running here and now. This creates an asymmetry in which young and middle-aged workers bear an increasing burden through taxes, social contributions and inflationary costs, without any certainty that they themselves will receive a comparable level of support in the future.

Demographic factors exacerbate this problem. Europe is rapidly ageing, birth rates remain below the level of simple population replacement, life expectancy is increasing, and the proportion of citizens of retirement age is growing in virtually every country on the continent. There are more and more pensioners per working person, which means a systemic increase in the burden on each taxpayer.

However, one of the reasons for the rapid growth of pensions in these countries is that pensioners are the main electoral group. They consistently participate in elections, actively express their views and directly influence the political survival of the ruling elites. As a result, any attempts at serious pension reform (raising the retirement age, changing the calculation formula, or shifting the emphasis to personal savings) face immediate resistance and often end in retreat by the authorities. For most politicians, the short-term loyalty of this group is more important than the long-term sustainability of the state model.

As a result, pension obligations are expanding in order to support voters, the fiscal burden is increasing, motivation to work and engage in entrepreneurship among younger generations is declining, economic growth is slowing, and citizens’ dependence on state redistribution is only increasing.