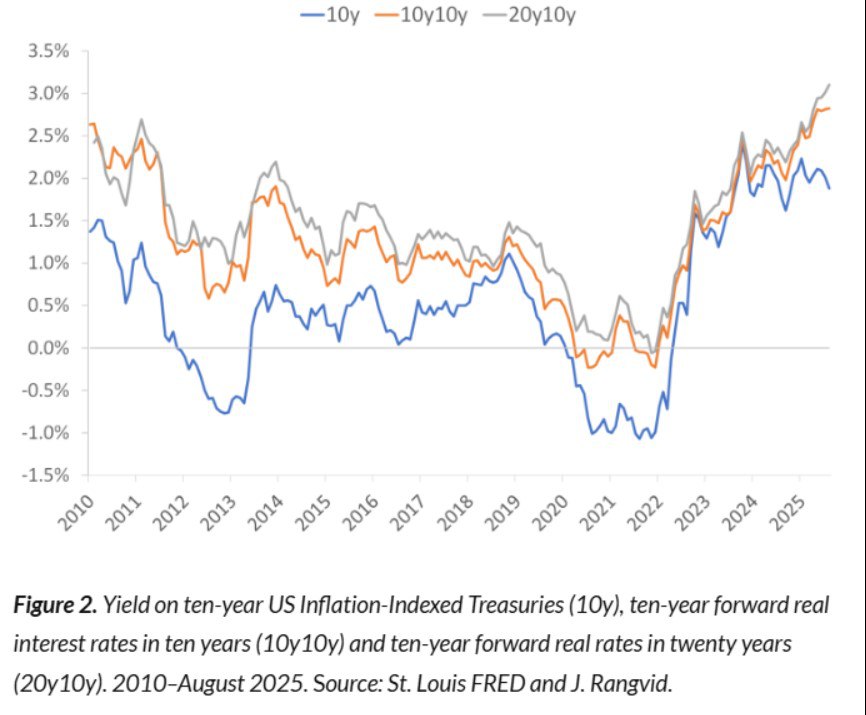

Today, the markets are signalling that the era of cheap money is over. The market’s expected real yield on 10-year US government bonds in ten years’ time is around 3%, which is the highest since 2010. This is roughly twice as high as at the beginning of 2023. Moreover, 20-year bonds are pricing in even higher real yields, which is an indicator of long-term tightening of financial conditions over the next decade. In other words, investors no longer believe in a return to the era of zero interest rates and cheap credit financing.

Europe

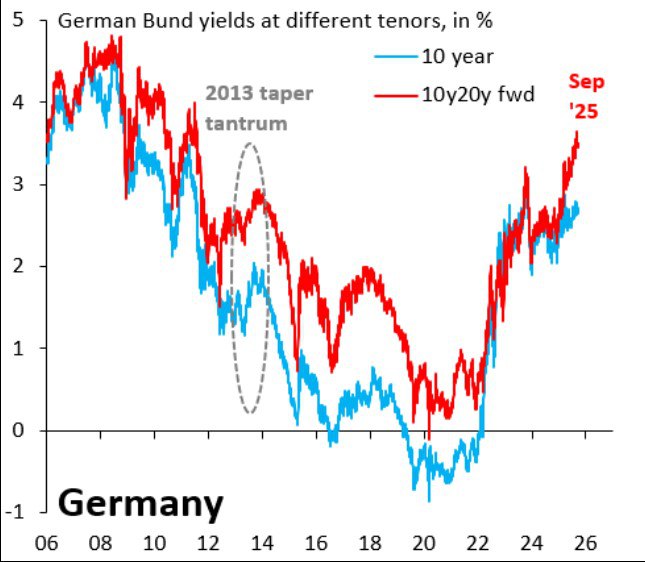

A parallel process is unfolding in Europe. Germany, traditionally regarded as an anchor of stability within the eurozone, is already seeing real Bund yields rise. This has been prompted by several factors: a chronic inflationary backdrop stemming from the energy transition and demographic pressure; the budgetary expense of industrial transformation and the militarization of industry; and a structural discrepancy between the ECB’s monetary policy and the shape of the labour market, which continues to overheat. As a result, the inflation-adjusted yield on 10-year German bonds is steadily settling in positive territory.

Russia

Russia is no exception to this trend, but rather part of a global trajectory. The growth in the real value of money is also evident in the Russian debt market. Inflation expectations remain high, but the Central Bank’s key rate is being kept at an elevated level.

In fact, we are witnessing a long-term global restructuring of the cost of capital. Corporate borrowers are forced to rethink their debt model. Consumer markets, including the mortgage segment, will slow down. Rate-sensitive assets such as real estate, venture capital and high-tech are being revalued downwards.