Japan was the first developed country to enter a state that demographers call ‘demographic maturity’ — a sharp decline in fertility and rapid growth in the proportion of the elderly population. Today, the total fertility rate (TFR) in the country is about 1.2 children per woman. Paradoxically, this figure no longer seems catastrophic. Many East Asian countries have even lower rates. For example, in China, it is 0.9–1, and in Europe (Italy, Spain and Poland), it is also around 1.1.

The only difference is that Japan has been living in a state of demographic maturity longer than anyone else. Accordingly, it is precisely this example that can be used to consider the long-term consequences for the economy and the labour market.

How is Japan restructuring its labour market?

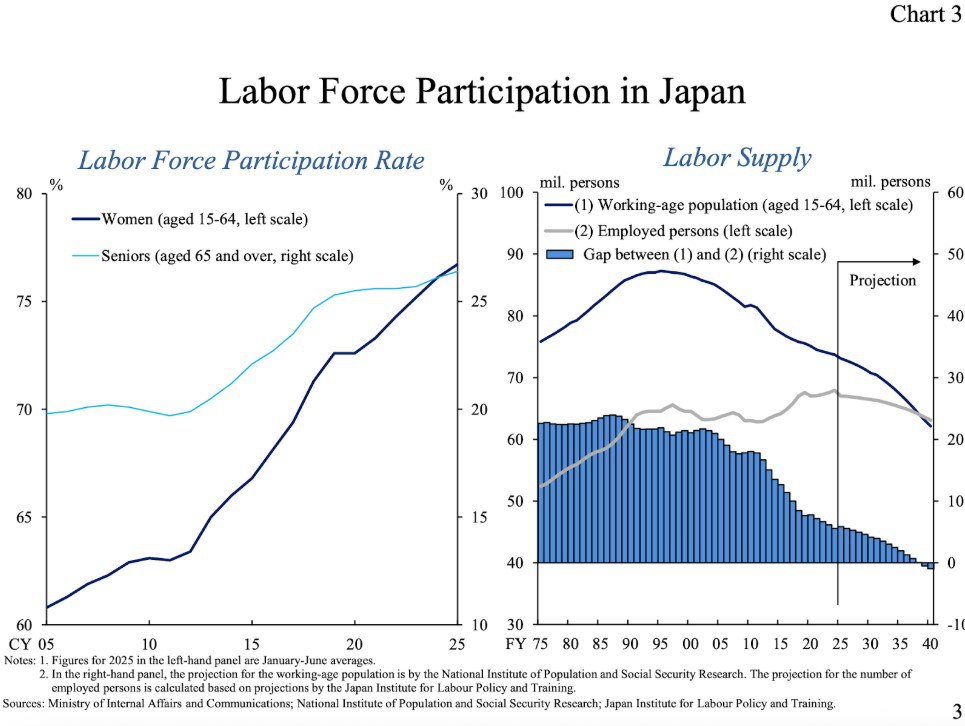

Since the early 2000s, there has been a noticeable shift. Women’s participation in the workforce has grown by 18% between 2000 and 2025. The reasons for this are the decline in fertility and the gradual disappearance of the traditional ‘housewife’ model. Thus, jobs that could have remained vacant due to the decline in population are being filled by women who are increasingly choosing careers over families.

Another important trend has been the return of older Japanese people to the labour market. Since 2012, the proportion of working seniors has grown by 7%. This is due not only to increased life expectancy, but also to changing attitudes among employers and society. Working beyond retirement age has become the norm.

Against the backdrop of an ageing society, Japan is demonstrating a phenomenon that is rare in Europe or the United States: the lowest youth unemployment rate in 30 years. There are so many jobs available that young professionals can choose their employer rather than compete for limited vacancies.

Japan remains one of the world leaders in production robotisation and automation. This compensates for the labour shortage. Unlike Europe, the country is extremely cautious about mass labour migration.

Some features of the Japanese approach:

- In a country with a population of over 120 million, the number of foreign workers has only recently exceeded 3 million.

- It is virtually impossible to obtain ‘political refugee’ status.

- Social benefits for migrants are minimal, and citizenship is difficult to obtain even after 10-15 years of living in the country.

- The main flow of newcomers is from East Asia (China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand).

Thus, Japan is solving the problem of labour shortages through internal reserves (women, the elderly, young people) and technology, rather than through the mass importation of migrants.

Today, many developed countries, from South Korea to Italy, have already entered or are entering a period of demographic maturity. Japan’s experience shows that the labour market does not collapse under the pressure of an ageing population, and that the involvement of women and older people in the economy can partially offset the demographic decline. Robots and technology are also becoming a critical factor. Strict migration policies are possible if domestic sources of employment are developed in parallel.